The beginnings: machines, newspapers, words by Zuzanna Kołodziejska-Smagała

Jews from Brody – preliminary identification by Justyna Lisak

The Biological Tragedy of Woman by Anton Nemilov by Anna Kałużna

Русский еврей - Some Basics by Anna Urbanowicz

The Changing Beauty Canon of a Jewish Woman in the Weekly Ewa by Anna Grygoś

The beginnings: machines, newspapers, words

Our project, which started at the beginning of September 2023, includes, among others: analysis of articles and -notes regarding the broadly understood body in the Jewish press in 5 languages: Yiddish, Hebrew, Polish, German and Russian between 1880 and 1939. We really have a lot of material to analyse. That's why we need to use digital humanities tools. Since many journals are available digitally in various virtual libraries, we assumed that computers would do much of the article selection for us.

Our project, which started at the beginning of September 2023, includes, among others: analysis of articles and -notes regarding the broadly understood body in the Jewish press in 5 languages: Yiddish, Hebrew, Polish, German and Russian between 1880 and 1939. We really have a lot of material to analyse. That's why we need to use digital humanities tools. Since many journals are available digitally in various virtual libraries, we assumed that computers would do much of the article selection for us.

WORDS

Therefore, we chose keywords related to the broadly understood body (the less obvious ones include: fresh air, walks, sanatorium, transitional age, desires, drives, hair, beauty contests, grey hair, wig, protective measures against pregnancy) and we have selected the press titles (excluding Hebrew for now) that we would like to use. To analyse the press in non-Jewish languages, we selected all titles available online.

NEWSPAPERS

However, we have to limit the number of magazines in Yiddish, so we have made a choice that would present representative and comparable materials in other languages. Hence, we have chosen journals that were published in large centres, such as Lviv, Krakow, Vilnius, Warsaw, Łódź, Poznań, as well as those from smaller cities and towns, taking into account their ideological profile. Our goal is to gather materials showing the widest possible cross-section of society, so we are also interested in magazines supporting specific political groups. For German and Russian, we limited the publication period to the end of World War I. When it comes to Russian and German, as expected, we do not have a large number of magazines published in Poland. In the case of German, there are currently 7 titles, and in Russian - 3. Thus, we selected titles that, although published outside the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, had a significant impact on the Jewish community living in the lands of the Crown, such as Die Allgemeine Zeitung des Judenthums.

However, we have to limit the number of magazines in Yiddish, so we have made a choice that would present representative and comparable materials in other languages. Hence, we have chosen journals that were published in large centres, such as Lviv, Krakow, Vilnius, Warsaw, Łódź, Poznań, as well as those from smaller cities and towns, taking into account their ideological profile. Our goal is to gather materials showing the widest possible cross-section of society, so we are also interested in magazines supporting specific political groups. For German and Russian, we limited the publication period to the end of World War I. When it comes to Russian and German, as expected, we do not have a large number of magazines published in Poland. In the case of German, there are currently 7 titles, and in Russian - 3. Thus, we selected titles that, although published outside the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, had a significant impact on the Jewish community living in the lands of the Crown, such as Die Allgemeine Zeitung des Judenthums.

When it comes to the Polish-language press, a rich and interesting source, apart from the quite obvious in this context, the only Polish Jewish women's magazine - the weekly Ewa (Eva) - will a bilingual (Polish and Yiddish) journal Krajoznawstwo Wiadomości ŻTK (Touring ŻTK News), published in the 1930s. The existence of the Jewish Tourist Society (ŻTK) shows the importance of the growing interest in tourism and sightseeing as an element of discourses on the body. The majority of Polish-language magazines were published in large urban centres - Warsaw, Krakow, Lviv, Vilnius, but smaller cities such as Kołomyja, Dubno and Tarnopol had also their Jewish journals in Polish. Their lifespan was often short, but they can be a valuable source for our research. The press obviously reflects the political situation. In the Kingdom of Poland and the Russian Empire, intensified publishing activity is clearly visible in the period immediately after the Revolution of 1905, when the tsarist authorities were forced to relax censorship and agree to the creation of social organizations, including unions for the emancipation of women1 . The interwar period saw a revival in the mid-1920s, before the crisis of 19292 and a decline in the number of Jewish magazines from the mid-1930s, caused by the economic crisis and growing anti-Semitism supported by systemic and state actions3.

When it comes to the Polish-language press, a rich and interesting source, apart from the quite obvious in this context, the only Polish Jewish women's magazine - the weekly Ewa (Eva) - will a bilingual (Polish and Yiddish) journal Krajoznawstwo Wiadomości ŻTK (Touring ŻTK News), published in the 1930s. The existence of the Jewish Tourist Society (ŻTK) shows the importance of the growing interest in tourism and sightseeing as an element of discourses on the body. The majority of Polish-language magazines were published in large urban centres - Warsaw, Krakow, Lviv, Vilnius, but smaller cities such as Kołomyja, Dubno and Tarnopol had also their Jewish journals in Polish. Their lifespan was often short, but they can be a valuable source for our research. The press obviously reflects the political situation. In the Kingdom of Poland and the Russian Empire, intensified publishing activity is clearly visible in the period immediately after the Revolution of 1905, when the tsarist authorities were forced to relax censorship and agree to the creation of social organizations, including unions for the emancipation of women1 . The interwar period saw a revival in the mid-1920s, before the crisis of 19292 and a decline in the number of Jewish magazines from the mid-1930s, caused by the economic crisis and growing anti-Semitism supported by systemic and state actions3.

MACHINES

A rather unexpected problem, unrelated to the research subject itself, but posing a serious challenge that appeared, was the poor quality of OCR in the materials we were interested in. OCR (Optical Character Recognition) is a technology that is used to optically recognize characters in scanned text. Thanks to it, it is possible to read the content of scanned source materials, which allows, among others, to search for keywords. Unfortunately, when trying to use digitized magazines available in Polish digital libraries, it turned out that the use of machine learning solutions (SML - Supervised Machine Learning) was highly difficult. One of the reasons is owing to the fact that the OCR layer of the documents was not correctly converted into text files. Fragments in press articles are often mixed up, words are not recognized correctly, and they are often combined or separated radomly. This greatly complicates the process of text extraction, recognition and analysis. Other technical problem often occurring is the way in which the text layer of digitized documents is made available - it is not adapted to machine reading. We are currently working on resolving these issues.

A rather unexpected problem, unrelated to the research subject itself, but posing a serious challenge that appeared, was the poor quality of OCR in the materials we were interested in. OCR (Optical Character Recognition) is a technology that is used to optically recognize characters in scanned text. Thanks to it, it is possible to read the content of scanned source materials, which allows, among others, to search for keywords. Unfortunately, when trying to use digitized magazines available in Polish digital libraries, it turned out that the use of machine learning solutions (SML - Supervised Machine Learning) was highly difficult. One of the reasons is owing to the fact that the OCR layer of the documents was not correctly converted into text files. Fragments in press articles are often mixed up, words are not recognized correctly, and they are often combined or separated radomly. This greatly complicates the process of text extraction, recognition and analysis. Other technical problem often occurring is the way in which the text layer of digitized documents is made available - it is not adapted to machine reading. We are currently working on resolving these issues.

Zuzanna Kołodziejska-Smagała

- Rochelle Goldberg Ruthchild, Equality & Revolution. Women’s Rights in the Russian Empire, 1905-1917 (Pittsburgh, 2010), 4.

- The world economic crisis began to affect Polish agriculture at the end of 1928, but it became fully visible in 1930 and lasted until 1935. (Antoni Czubiński, Dzieje Najnowsze Polski do roku 1945 (Poznań 1994), 364-365)

- State-regulated anti-Semitism is well demonstrated in Natalia Judzińska's book, Po lewej stronie sali. Getto ławkowe w międzywojennym Wilnie (Warsaw, 2023).

Jews from Brody – preliminary identification

Although it's hard to believe, six months have passed since the launch of our project. As scheduled, we have devoted the last months to searching for press titles that meet the adopted criteria determining the time and territorial scope of the research and to trying to apply machine learning solutions (SML – Supervised Machine Learning) in working with press sources. We wrote about it in the previous post. We treat the use of digital humanities tools and methods for press analysis in the project as a complement to qualitative research.

"Jerusalem of Austria-Hungary"

The involvement in the project "Discourses on Body in Jewish Culture in the Polish Lands between 1880-1939" requires a significant degree of flexibility. This is due to the diversity of both the sources analyzed and the research methodologies we use. In my case, this flexibility means in practice the transition in recent weeks from a press query to studying the Jewish history of the city of Brody (Lviv Oblast, today's Ukraine), relying on sources as diverse as: literature, ego-documents and reportage.

The image is taken from the book Brody: Eine galizische Grenzstadt im langen 19. Jahrhundert

Börries Kuzmany, Vienna 2011.

Brody, which the Emperor Joseph II Habsburg used to call ‘modern Jerusalem’1, was initially part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. As a result of the First Partition of Poland (1772), the city came under the rule of the Habsburgs. From 1779, the Austrian-Russian border ran through Brody. In result the city became an important trading point, and in the same year it obtained the privilege of a free trading city from the emperor Joseph II2. Already in the nineteenth century, 88% of the population of Brody was of Jewish origin. At that time the city became an important centre not only of the Jewish enlightenment (Haskalah), but also Hasidism. The strong influence of the Haskalah, which spread the ideas, such as: productivity, loyalty to the state and its ruler, secular education, and learning secular languages3, among the inhabitants of Brody resulted from the activities of local merchants who maintained trade contacts with Frankfurt am Main, Leipzig or Breslau. The spread of Enlightenment ideas among the Jews of Brody meant that this group gradually became closer to German culture. The domination of the German language and culture in Brody, which began in the first decades of the nineteenth century and resulted from the popularity of the Haskalah, began to gradually give way to the re-Polonization of Galicia in the late 1860s. This process was facilitated by a large group of Brody maskilim – the supporters of the Jewish Enlightenment, who recognized the need to aspire to a new, locally dominant culture. The re-Polonization of Galicia was caused by a number of socio-political rights that were granted to this region between 1860 and 18734. Although, as a result of the reforms, over time the access to Polish culture was gradually supported by a bigger number of Jews5, this does not change the fact that in the nineteenth century the Jewish inhabitants of Brody were strongly influenced by the German language and culture. Although the maskilim community externally aspired to the culture of the Habsburg monarchy, in many households these were the ties with the Polish language that were still maintained. This is clearly shown in texts by Adela von Mises and Josef Ehrlich. They are both authors of memoires from their childhood and adolescence in Brody. Their texts were translated from German into Polish and published in the book series Jews. Poland. Autobiography6, that for several years has been edited by Professor Joanna Degler, a member of our team.

https://zydzi.autobiografia.uni.wroc.pl/adela-von-mises/

Adela von Mises, whose ancestors came from the most influential Brody families - the Landau and the Kallirs, captures in her memoires the spirit of the maskilim houses, while Josef Ehrlich, in his Memories of a former Hasid, describes life of a Hasidic family. Both Von Mises and Ehrlich talk about taking Polish classes at home, which proves the attachment of the Brody Jews to both cultures. This fact makes Brody an important center on the map of our project. Reading the memories of Ehrlich and von Mises makes for me a valuable introduction to the history of Jewish Brody in the nineteenth century and enables me to trace the process of acculturation of Brody Jews to the German language culture. Since Brody was considered ‘the most Germanized city in Galicia’7,I will try to analyze discourses on the body and sexuality in such sources in German as: the press, literature, ego-documents and reportages using the example of this city. Looking at Brody as one of the centers of German-speaking culture created by Polish Jews will allow me to build a research perspective that I will be able to use in an analysis of other places. The literary texts by Joseph Roth, who was also born in Brody8 and pamphlets of the time, such as Sisyphus: Gegen den Mädchenhandel: Eine Studie über Mädchenhandel und Prostitution in Osteuropa und dem Orient by Bertha Pappneheim or Fünf Wochen in Brody Unter Jüdisch-Russischen Emigranten. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der russischer Judenverfolgung by Moritz Friedlender, will certainly also be valuable sources of knowledge and contexts.

„Grolich’s milk will rejuvenate your hair"

Finally, a few words about interesting discoveries I made during the press query in the first months of my involvement in the project. When I was initially reviewing the content of Jewish magazines published in the Polish lands (the lands of the so-called German and Austrian partitions) in German until 1939, one of the titles aroused my particular interest due to its rich graphic design. It was Die Jüdische Volksstimme9 [The Jewish Voice of the People],) and its extensive advertising section. The magazine was published between 1900 and 1934, initially in Brno, and later also in Vienna, Budapest, Prague and Lviv. It had a Zionist profile and was addressed, as the subtitle indicated, to workers and sales reps. Due to the latter group of readers, the periodical contained an extremely rich advertising section. A significant number of advertisements published in the magazine covered such areas like: fashion, beauty, health and health care, which are definitely part of the discourses on the body. Advertisements that readers of Die Jüdische Volksstimme could come across promoted fashion houses, beauty salons, medical clinics, and even cosmetic and pharmaceutical products. Many of the advertisements published in the journal did not have only eye-catching graphics, but also a detailed description of the advantages of the advertised products. Extensive advertising content covering several pages of each subsequent issue of the magazine allows us to capture the spirit of the era, manifested in the way of thinking about the matters important for our project, such as personal hygiene, healthy diet and physical exercises. A modern reader may be surprised by the inconsistency of the content of ads published in Die Jüdische Volksstimme. Some of them seem to be extremely modern even today, while others seem to belong to a long-gone era. On the one hand, the magazine promotes beauty salons providing hairdressing and cosmetology services similar to today’s such services. On the other hand, the newspaper regularly publishes advertisements of carbonated (soda) water, which at the time was perceived as a medical product with versatile properties and as such was widely sold in pharmacies. The in-depth quantitative and qualitative analyses of adverts published in Die Jüdische Volksstimme enable us to observe which of the promoted ideas can be still considered valid today, after over a century, and which should be attributed to an era long gone. This type of observation will certainly be valuable for the research conducted by our team.

Justyna Lisak

- Agata Rybińska, "Wstęp" [Introduction], in: Josef Erlich, Droga mojego życia. Wspomnienia byłego chasyda [My way of life. Memoires of the ex-Hassid], trans. Agata Rybińska (Warsaw: PWN, 2022), XXIV.

- Virtual Shtetl, Brody – a history of the community https://sztetl.org.pl/en/towns/b/925-brody/99-history/137121-history-of-community; Virtual Shtetl, Brody https://sztetl.org.pl/en/towns/b/925-brody

- Marcin Wodziński, Haskalah and Hasidism in the Kingdom of Poland. A History of Conflict (Oxford: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2005), 49.

- Historiography calls this process as Autonomy of Galicia One of the most important reforms introduced between 1860 and 1873 was the introduction of Polish as the official language of the administration and jurisdiction in Galicia in 1869. Virtual Shtetl – Autonomy of Galicia https://sztetl.org.pl/en/glossary/autonomia-galicyjska

- Maria Antosik-Piela, "Wstęp" [Introduction], in: Adele von Mises, Ciotka Adela opowiada… [Aunt Adela tells a story], trans. Lidia Jerkiewicz (Warsaw: PWN, 2023), XXII.

- See: https://zydzi.autobiografia.uni.wroc.pl.

- Virtual Shtetl, Brody – a history of the community…

- Agata Rybińska, "Wstęp" [Introduction]…, XXIX.

- The journal is available in a digitized form in the collections of the Goethe University in Frankfurt and on the website of the Austrian National Library.

The Biological Tragedy of Woman by Anton Nemilov

When working with source texts in Yiddish, the first book that we took was Anton Nemilov's book: Biologisze tragedie fun der froj [The Biological Tragedy of Woman].It was originally published in Russian in 1925 in Kiev, and interestingly, the Yiddish translation preceded the Polish one by four years. The fourth (!) Russian edition of the book was translated into Yiddish by G. Yashunsky. It was published in 1929 by the ‘Kultur Lige’ publishing house in Warsaw. The book was published in Polish and translated by Alicja Krasnobród in 1933 by the ‘Metropolis’ publishing house. The Hebrew translation was also published in Warsaw in 1931 by the Zionist youth organisation Hashomer Hatzair.

The author, Anton Nemilov, was an outstanding Russian scientist, doctor of medicine, histologist, who was a student of Professor Aleksander Dogel. Both were associated with the University of St. Petersburg.

The author, Anton Nemilov, was an outstanding Russian scientist, doctor of medicine, histologist, who was a student of Professor Aleksander Dogel. Both were associated with the University of St. Petersburg.

Nemilov himself focused his research interests on neurohistology and histophysiology (i.e., the science of the structure and functioning of tissues examined microscopically), with particular emphasis on the histophysiology of the reproductive system in the general biological aspect. Apart from being a great scientist, he focused his energy on issues related to teaching and popularizing science. He wrote a number of articles and books that gained enormous popularity in the twentieth century. His works have been translated into many languages. The most famous of them was the aready mentioned The Biological Tragedy of Woman.

The book turned out to be revolutionary. It was widely read and commented in the press. It appeared in discussions and even autobiographical literature. Threads about The Biological Tragedy of Woman appear, for example, in Chava Rosenfarb's autobiographical novel entitled Briv tsu Abrashen (Letters to Abrasha), whose young heroines, adolescent girls, read Nemilov's work and argue with his theses. It is also incidentally mentioned in Józef Hen’s autobiographic novel Nowolipie (Novolipie).

The main theme of Nemilov's deliberations (apart from issues closely related to the process of body development and sexual maturation) is the suffering of a woman, which has been permanently embodied in her existence through the role imposed on her in the process of reproduction. The author's sad reflection appears at the very beginning of the book. He made it clear that there was no escape from this role. Woman was created only to perpetuate the species. Nemilov clearly emphasizes that there is no such thing as pleasure from motherhood. This is only an illusion. A pregnant woman is nothing more than an incubator. In his book appears also the idea of man as a living machine, deprived of its own will, reproducing the ongoing process of reproduction. Nemilov weaves into his scientific arguments a new, post-revolutionary idea of the human body as a perfectly functioning machine. This innovative image of female body in particular is set in opposition to capitalist eroticism, here perceived as vulgar.

Although one can argue with the thesis of Nemilov's book, it undoubtedly had educational value as it described precisely the biological processes taking place in the human body. And in fact, Nemilov succeeded in that regard comprehensively explaining the way human body functions at the cellular level. However, he did not avoid folk wisdom and scientific quotations that sometimes might seem funny, at other times they give a reader goosebumps. One can find, for example, arguments that are indicating that a woman is not a human at all, just like a hen (to paraphrase the well-known Russian, but also Polish saying, which appears in many variations: A hen is not a bird, Poland is not a foreign country [kura to nie ptica Polsha nie zagranica]) is not a bird. Nemilov sometimes even recalls the words of the American scientist Dr. Keler, who writes that the ideal of marriage is life with a ‘castrated’ woman and only such a relationship has a chance for a relatively happy and peaceful life. In any other case, a woman becomes subordinate to her biology and primarily strives for reproduction.

The image of a woman emerging from Nemilov’s work brings to mind a puppet, a doll controlled by biological processes. A woman can only free herself from them by undergoing menopause. So, dear ladies, chin up, not all is lost. We can also finally become people. Right after turning forty.

Yet, joking apart, this book provides a vast range of medical and everyday vocabulary related to the body, and offers insight into the discourse on the female body adopted from Russian into Yiddish, and that is what we are aiming for.

The image of a woman in Niemiłov’s book has an anti-feminist tone. It deviates from the revolutionary assumptions of equal rights and an idea of an equal woman, who is a significant member of society and who, alongside men, contributes to the development of civilization. The author argues that even economic independence does not free women from the biological yoke of gender. This perspective objectifies women, reducing their social roles to merely that of an incubator, a children factory. The role of men, by contrast, is not limited only to a biological reproductive function or instinct. They are active and dynamic actors on the stage of history. In this regard, Niemiłov supports the views of Otto Weininger, who tried to prove the inferiority of women in comparison to men and in that way to solidify the legitimacy of male dominance in the society of the time.

Anna Kałużna

Русский еврей - Some Basics

I have become interested in the magazine Russkii Evrei because I am writing my MA thesis entitled Hygiene in the Russian-language Jewish Press between 1879 and 1884, under the supervision of Professor Agnieszka Jagodzińska. My thesis will analyse the following newspapers: Voskhod (the East), Evrejskaja Biblioteka (Jewish Library), Rassvet (The Dawn), Evrejskoje Obrozienije (Jewish Review) and Russkii Evrei (Russian Jew). I started my research with the latter, because it was there that I found the majority of descriptions of hygienic conditions in hospitals, cheders, etc., as well as short texts presenting the physical and mental condition of patients.

Russkii Everei: Eženedĕl’noe izdanіe (Russian Jew: Weekly Scripture) was a Jewish weekly in Russian. It was published between 1879 and 1884 in Saint Petersburg. On March 15, 1879, Lazar Berman obtained consent from the Main Press Board to launch a newspaper title1. The magazine was printed in the printing house of L. J. Berman and H. M. Rabinovitch at Izmajlovskiy Prospekt no 7, apartment no 12. The magazine was sold, among others, in Moscow, Vilnius, Minsk, Grodno, Brest-Litovsk, Kremenchuk, Odessa, Kiev, Kherson, Kharkov, Bialystok, and Warsaw. The price of one issue depended on the subscription period and place of residence. An annual purchase in St. Petersburg cost 6 rubles, a half-yearly purchase cost 8.50 rubles, and a quarterly purchase cost 2 rubles2. Abroad, prices were twice as high. The volume of one issue was 15-20 pages, but from 1884 onwards - 15.

Russkii Everei: Eženedĕl’noe izdanіe (Russian Jew: Weekly Scripture) was a Jewish weekly in Russian. It was published between 1879 and 1884 in Saint Petersburg. On March 15, 1879, Lazar Berman obtained consent from the Main Press Board to launch a newspaper title1. The magazine was printed in the printing house of L. J. Berman and H. M. Rabinovitch at Izmajlovskiy Prospekt no 7, apartment no 12. The magazine was sold, among others, in Moscow, Vilnius, Minsk, Grodno, Brest-Litovsk, Kremenchuk, Odessa, Kiev, Kherson, Kharkov, Bialystok, and Warsaw. The price of one issue depended on the subscription period and place of residence. An annual purchase in St. Petersburg cost 6 rubles, a half-yearly purchase cost 8.50 rubles, and a quarterly purchase cost 2 rubles2. Abroad, prices were twice as high. The volume of one issue was 15-20 pages, but from 1884 onwards - 15.

The first editor was Lazar Yakovlevich Berman (1830-1893), who ran the magazine until October 21, 1883. Later, he was replaced by Lev Osipovich Kantor (1849-1915). The publishers until 1883 were Lazar Berman and Hirsch Meyerovitch Rabinovitch (1832-1889), and then Rabinovitch himself.

Lazar Yakovlevich was a teacher, social activist and a founder of the first Jewish school in Saint Petersburg3. Between 1869 and 1882 he lectured Jewish law at a girls' high school. Hirsch Rabinovitch, in turn, was a publicist and social activist. In the 1870s, he opened a printing house in St. Petersburg, where Jewish books in Russian were published4. Lev Kantor was a writer and a doctor of medicine and a rabbi in Liepaja (1890-1904), Vilnius (1905-1908) and Riga (1901-1915)5. He wrote reviews of Jewish literature and critical essays in such magazines as Evrejskaja Biblioteka and Voskhod. In St. Petersburg, he published the first Hebrew daily Ha-Yom (Today), and between 1888 and 1889 he edited the newspaper Ha-Melits (The Advocate) and the Yiddish weekly Dos Yidishe Folksblat (Jewish People's Newspaper)6.

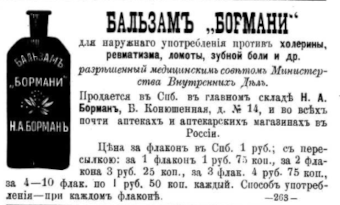

Russkii Evrei, No. 12, March 19, 1880, p. 20

The advertisement promotes the "Bormani" balm, which cures, among others: rheumatism, pain, or cholerine. It says: You can buy it at the main plant of N. A. Borman and in all pharmacies and pharmacy stores in Russia. In St. Petersburg, the price for 1 bottle is 1 ruble, two bottles cost 3 rubles.

It is used for daily use against cholera, rheumatism, various pains, toothache, etc.

Russkii Evrei was a general interest magazine, which covered many genres. It explored such fields of interests as: current affairs, government arrangements, fragments from court chronicles, local chronicles, columns, scientific texts, poetry, fragments of short stories, for example a translation of the novel Eli Makover by Eliza Orzeszkowa, press reviews, correspondence from the Empire and abroad, letters to the editor, classified ads, advertisements and obituaries. The ads promoted such products as, for example: bromine water, siphons for carbonated water, tutoring, Hebrew translators and food products. The weekly provided information on, among others: hygienic and sanitary conditions in schools, cheders, hospitals, issues related to conversion, pogroms, education, military service and charity events, the latter organized mostly by women. Additionally, announcements from governmental institutions, minutes of meetings, reports of social organizations, reports on immigration and Jewish settlement in Palestine, as well as articles on public events were published7. In the final years of publication of the magazine, the number of advertisements and announcements in the weekly increased. It may have been caused by the financial difficulties and the approaching end of the newspaper's publication.

At this stage of research, in the magazine in question, the concept of "body" is compared with generational changes and transitions in thought towards modernization. One of the articles talked about fashion changes among younger generation. Young people did not want to dress like their grandparents or even fathers. Jewish girls were increasingly inspired by the latest non-Jewish fashion. In this way, they cut themselves off from the traditional lifestyle. It is worth emphasizing that the author of the article approved of such changes.

Anna Urbanowicz

The author is a student of MA studies at the Taube Department of Jewish Studies, University of Wrocław and will soon defend her master's thesis at the Institute of Art History, University of Wrocław.

She is preparing her master's thesis on hygiene in the Jewish press in Russian between 1879 and 1884, under the supervision of prof. Agnieszka Jagodzińska. She was one of the organizers of the What's new in ‘Niderschlezje’ project? The history of the post-war Wrocław Jewish magazine and publishing house ‘Niderszlezje’ financed under the FAST 2023 program. She took part in tagging the texts of the corpus of Professor MarcinWodziński’s project Two Enlightenments: Poles, Jews and their path to Modernity.

- Dmitrij Arkad'yevich Eliashevich, “Epocha ‘priznanija nieispravimosti’ (cenzura evrejskih izdanij v Rossii 1882-1914 gg.)” [in:] Pravitelʹstvennai͡a︡ politika i evreĭskai͡a︡ pechatʹ v Rossii, 1797-1917: Ocherki istorii t͡s︡enzury (St Petersburg-Jerusalem, 1999), 408.

- Russkii Everei: Eženedĕl’noe izdanіe no. 1, January 2, 1880, p.1.

- Margolis Aleksandr Davidovič, Berman Lazarʹ Jakovlevič (1830 - 1893), pedagog, izdatelʹ, obŝestvennyj dejatelʹ, http://jewishspb.com/article/1382890 [accessed: May 19, 2024].

- Lukin Veniamin, Rabinovič Girš ((Cebi) (1832 - 1889, SPB), literator, izdatelʹ, obŝestvennyj dejatelʹ, http://jewishspb.com/article/1382890 [accessed: May 19, 2024].

- Margolis Aleksandr Davidovič Kantor Lev Osipovič (Iehuda Lejb) (1849 - 1915), ravvin, pisatelʹ, obŝestvennyj dejatelʹ, http://jewishspb.com/article/1377445 [accessed: May 19, 2024].

- Ibidem.

- Rec Julija Sergeevna, "Russkii evrei", eženedelʹnik, 1879 – 1884, http://jewishspb.com/article/1371592. [access: May 18, 2024].

- N. Rajtlier, Wysoko-Litovsk: Korespodencija Russkogo Jevrereja: Rawnodushije k vospitaniyu, otsutstvije uchiliszcz, Russkii Evrei 1880, (no. 11): 5.

The Changing Beauty Canon of a Jewish Woman in the Weekly Ewa

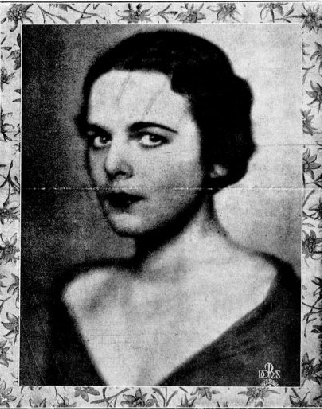

Zofia Batycka - Miss Polonia 1930

"Ewa" no 6 (1930), 1

My research focuses on the Warsaw-based Jewish women's magazine Ewa, which was published in Polish between 1928 and 1933. What interests me most is the changing canon of beauty of a Jewish woman; the extent to which they tried to catch up with the non-Jewish world without losing their own selves. Ewa, like other modern women's periodicals, published articles on politics, culture, art, feminism, and the body. Although the women authors - and less numerous male authors - of the texts printed in Ewa supported the Zionist ideals, the newspaper avoided political content, focusing primarily on social issues and issues related to feminism1. As the choice of language may seem surprising, it was a tool to re-incorporate into active political life those members of the Jewish community that had left it for various reasons. The Polish language turned out to be crucial in rebuilding Jewish national identity2. As Maria Antosik-Piela points out in her article, "’Taming from a distance.’ Polish-Jewish literature and the Zionist vision of territoriality", the failure of the idea of Jewish integration and harmonious coexistence of both social groups slowly became clear to Polish-Jewish writers and publicists of that time. The increasingly frequent attacks on Jews awakened in them a ‘sense of separateness and racial pride.’ However, those writers, rejecting ‘Polish speech in favor of Hebrew’eventually, because they were deeply embedded in the Polish culture, used Polish todescribe Palestine as a chosen place and a new homeland for the Jewish nation3.

Issues related to the concept of the body opened up wide thematic possibilities, which included not only fashion, cosmetics and physical education, but also birth control (including abortion), women trafficking, and sexuality. Already in the first issue, conscious motherhood was one of the leading themes. According to Paulina Appenszlak (the editor-in-chief), woman was the one to decide how many children she could have so to raise themto make them exemplary citizens of the future state of Israel. If she was unable to raise another child, she may have decided to have an abortion. The editors recommended abortion carried out by a doctor than a self-management. By proving that abortion was just an ordinary medical procedure, they tried to stop stigmatizingit, so that the readers did not have to risk their health or lives.

The interwar period in Poland was an ideal place for the development of new movements and ideologies. Zionism and communism (both were changing the society, but I focus on Zionism), provoked shifts within the canon of beauty.Because they promoted movement, physical strength and, to some extent, the emancipation of women, they were indicating what kind of body a woman should have. A woman should be strong, physically and mentally, which meant that she was supposed to have knowledge that she could use well for the development of herself and her loved ones, and thus become a role model for the future nation.

Another topic that aroused my curiosity, are advertisements for plastic surgery and cosmetics in the weekly. It can be noticed that with the development of cosmetology and the spread of fashion, there was an increase in the promotion of the culture of the 'perfect body': without wrinkles, freckles, discolorations or body hair. It was also the case in Ewa. Some issues contain advertisements recommending a new treatment that helps firm the body or get rid of gray hair. There are also articles written by Helena Brzezińska - the owner of the famous Izis beauty parlor. These articles were sponsored, which means that it was not about simple advice for a woman reading the magazine, but about persuading her to undergo treatments that she might not necessarily needed, but were required by the fashion that the magazine's reader was supposed to follow. It is clear that Ewa touched on a variety of topics. This is what distinguished it from other women's Jewish newspapers, because not all of them had such a wide field of interest. Their goal was to reach as many Jewish women as possible, to allow them to see more and know more, thereby getting to know themselves.

Anna Grygoś

The author is a first-year master's student at the Department of Jewish Studies at the University of Wrocław. She is writing her master's thesis entitled: "The Changing Beauty Canon of a Jewish woman on the example of Ewa weekly”, under the supervision of Dr Zuzanna Kołodziejska-Smagała. She also completed her bachelor's degree at the Department of Jewish Studies, her thesis was entitled: "Love, Death and the Sacred. The Poetry of Cela Dropkin". She is interested in women's poetry and research on the place of Jewish women in tradition, religion and culture.

- Appenszlak Paulina, https://sztetl.org.pl/pl/node/192191, [accessed: 15.06.2024]

- Monika Szabłowska-Zaremba, Portrait of a Zionist from the pages of Ewa, andTygodnikdlaPań (1928-1933)” [in Polish], Lublin, 2015, p.546-547

- Maria AntosikPiela, "Taming at a distance. Polish-Jewish literature towards the Zionist vision of territoriality",[in Polish]Przeglądhumanistyczny 4, 2015, pp. 78-79. [access: 12/07/2024]

- https://warszawa.etnograficzna.pl/pl/praha/nasz-przeglad#fn-2, [access:15.06.2024]

- Monika Szabłowska-Zaremba, "Portrait of a Zionist", Lublin, 2015, p. 550-551

- Aleksandra Ciejka, Fashionable body through the centuries. Cultural analysis of the model's body,[in Polish], Łódź, 2015, p. 149-151

- Helena Brzezińska, https://historiaposzukaj.pl/wiedza,historiomat,1393,historiomat_izis_leczy_i_upieksza_legendarny_salon_kosmetyczny_i_jego_neonowy_szyld.html [access: 15.06.2024 r.]

- Ewa, no 13, (1930), 4, https://polona.pl/item-view/401d0e9e-f72f-42fe-8435-779dbc363ee5?page=4 [access:15.06.2024]

- Ewelina Kogut, Ewa content bibliography [in Polish], access date: 2024 [accessed: 12/07/2024]

- Monika Szabłowska-Zaremba, "Portrait of a Zionist…", p. 551-553.